Algo para traducir

Where poets, writers, translators and publishers cross paths

Made in Spanish

El desahucio - Jesualdo Jiménez de Cisneros Quesada

Chocolate con veneno - Desiderio Vaquerizo

On 31 August 2015, a report issued by Spanish Home Office[1] provided the figure of 359,193 women who were confirmed to be victims of domestic violence in Spain to date that year. A figure which is practically four and a half times more than the capacity of the Santiago Bernabéu football stadium. That’s easy to say.

In 1979 Spain was in its period of transition. ETA caused the death of 79 people, the far right military circles were already considering a coup d'état, Catalonia and the Basque Country had their autonomy statutes approved, the UCD internal crisis already anticipated the electoral defeat in 82 and in a village in deep Extremadura, a girl named Etelvina escaped an eternal hell of abuse, full of beatings, screaming and silence.

Etelvina had grown up happy, you could even say she was free, within what it meant to be free for a young girl in the seventies. That was until she fell in love and she couldn't see the signs that warned her of the storm (or the hell) that was approaching. Etelvina grew up with her grandparents and she didn't lack love or support from her friends. But when the wind blew, she could only put on a brave face through the silence, even though the injuries, the bruises and the shine escaping her face spoke for themselves. As a good daughter of her time, during bad times, put on a brave face. She kept it all to herself.

Etelvina’s children were her driving force to live, her anchor in this world. United by an invisible link of love, understanding and justice, you could find Inocencia and Áurea around Etelvina, who were her support, her escape route, her saviour. Tomás was the animal. He was even worse than an animal, as animals don’t usually inflict pain because of their insecurities or cowardice.

Chocolate con veneno starts with the writer who narrates the story meeting his main character; a confident, direct and grounded Etelvina. Desiderio Vaquerizo makes use of the first person in Etelvina's story with such passion that it becomes a very personal and harrowing story. It's a story that takes your breath away. Etelvina's words repeatedly beat her readers. They become accomplices to her experiences, outsider witnesses to the treatment she endures.

The day to day of the homicide detective is developed parallel to the narration of the events that shape Etelvina's character. That is until her destinies join to reveal the ending of the story, Etelvina’s ultimate destiny.

Desiderio Vaquerizo transports us to a deep, real Extremadura of that time. She brings together sayings and expressions that used to be very common among older generations and which are being increasingly neglected. So we can read “cuando marzo mayea, mayo marcea” (”when it’s March it’s May and when it’s May it’s March”) or “Virgencita, Virgencita, que me quede como estoy” (”My Lady, my Lady, let me be as I may”). Desiderio transcribes the accent of the place, for example, the elision of the final ‘s’ and he reproduces letters written by the villagers, packed with spelling mistakes. However, all of these characteristics, some of them considered very serious mistakes due to grammar or Spanish spelling, transmit simplicity and warmth. They incite the reader to appreciate and admire those women who have grown up with a scarcity of means but have known how to establish connecting links that only death separates. The reader learns to value those circumstances, the lifestyles of the main characters in Chocolate con veneno and ends up identifying with them, loving them (to those who deserve it, of course).

Orioles are birds which are golden yellow mixed with black. Their flights are short and quick. And this is how our other main characters move, Inocencia, Inmaculada, and Áurea, golden. Their quick, short flights will be fundamental. Vaquerizo retains the mystery and the true sense of these flights right to the end with finesse and elegance.

Spain was Catholic to the core at that time and as such Vaquerizo echoes this characteristic, not only in the expressions that his characters use, but also in the way that he unveils the reality of the facts. This is through “mysteries” (of the rosary) that are revealed little by little, producing a feeling of anguish and worry within the reader towards the main characters of this episode of domestic violence.

The author puts the urban world face to face with the rural world. However, this is a friendly confrontation in which the homicide detective delicately, being conscience that “he has seen more of the world”, uses his tact and his experience to access a world generally closed off to strangers.

The writer of the story closes the book as an epilogue to express what is implied when meeting a woman like Etelvina, listening to her story and writing about it afterwards. It is a perfect ending worthy of a novel that is so shocking, so real, so emotional that is Chocolate con veneno.

They say that Etelvina is a Germanic name which means faithful and noble. In this case they aren't wrong. Our Etelvina was faithful (in the sense of what she believed was faithful) until the very end, to her husband, her children and her friends. Our Etelvina was noble, she never wanted anything bad to happen to anyone, not even the instigator of her torment. Our Etelvina was as hard as a rock, she didn't care about the beatings, the blows or the insults she received, with or without help, she always got up.

However, don’t get that wrong, as a reader, you will love Etelvina and you will cry together, but you will also get angry with her.

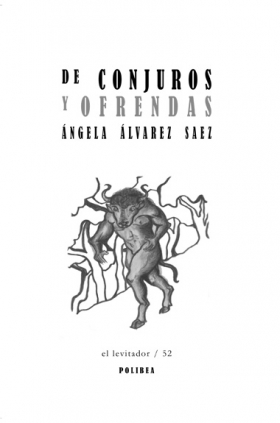

De conjuros y ofrendas - Ángela Álvarez

Ángela Álvarez’s poetry certainly carries us to other spaces, as if we were travelling on Aladdin’s magic carpet. It takes us to ancestral places, like Ithaca or Ancient Egypt, with its sphinxes and its glorious Alexandria; to steamy Andalucía with one of its eternal cities, Córdoba, symbol of the three cultures; and to exotic places, like Africa or the Persian cities. It also makes us navigate the waters of the Nile and over the Adriatic, making a brief stop at the Acropolis.

Ángela Álvarez breaks down the barriers of time and space. Not only does she cross geographical borders in her poems, but she also goes beyond historical and cultural borders. She brings us back to mythology, oft-forgotten and reserved to the study of the Classics, through Charon and the Minotaur, which becomes a fundamental symbol in her poems and its presence is found throughout the book. Different cults and customs remind us of the various ways in which the expression of feelings comes alive: from the Vestals to the Hindus, passing through the Sagrada Familia or the Japanese tea ceremony.

Her poetry is bleeding, wild, visceral. Her poetry is graphic, visual, descriptive. Ángela Álvarez turns to the past in search of answers, to find her identity, to define herself as a writer, to express how her poet’s soul rises up and, as such, she reflects the avid existential search for answers, trying to find them in memories and experiences of the past.

She presents us with a wild world where the presence of animals is constant and the need for rituals becomes primordial, a world where verses are impetuous, a world filled with hunting, blood, carnal encounters, fangs, worry, beasts, fear, the wild, all the things that cannot be tied down.

This savage world is at once magical and real. Love and fear oppose each other, internal fears are conquered by love, which also creates pain, brought about through spells. The empty being opposes the existential search to find itself, the loss of innocence casts back to the past to find refuge in what mothers provide for their children. Childhood is essential for learning and finding oneself as an adult being. Life is a cycle, a magic spell of birth and creation that happens time and time again. Time appears as a constant passing, occasionally tedious. Sadness, melancholy and weeping make themselves present to make way for the hope of new generations. The rhythm of this poetry gives wings to the spirit, allowing it to fly and liberating the imprisoned soul.

Land and sea, symbols of wisdom and the origins of life, are two constants in the poetry of Ángela Álvarez. Twilight and forests are the time and place she returns to with her verses in order to create armies of words. The tiger would be her animal and blood red, her colour.

It is characteristic of the author to place verses in italics and with this she introduces a second voice in the poem which acquires a life of its own as a thinking, feeling element.

Arte mayor verses predominate, switching to arte menor – including verses consisting of a single word – to increase the pace, the suspense, and to highlight the importance of certain elements.

Ángela Álvarez’s verses shake us up and down and turn the world we know on its head. Her short poems, though their brevity doesn’t make reading them any quicker, impregnate the reader’s reasoning and comprehension and do not let go until they are no longer understood. The depth and density of her poetry force you to read her verses again and again, without tiring, until they come to a life of their own through plastic images. Because Ángela Álvarez’s poetry is, above all, plastic, like the Goya painting that she mentions in the poem “Antártida”. Reading her poems brings a constant succession of images, blurred between the real world and illusion.

Ángela Álvarez masterfully mixes abstract vocabulary with concrete concepts, the material with the ethereal, creating a new language filled with visual images that stand out for their originality. After the slow and reflective reading of each verse, of each poem, images arise styled after the squares of Neoplasticist Piet Mondrian, who intended to “strip away all of art’s accessories”. And that is Angela Alvarez’s poetry: pure art free from banal decorations.

Ángela Álvarez’s therefore places herself at the avant-garde of poetry. Her poems recall creationist poets of the likes of Gerardo Diego and Vicente Huidobro because, like them, the writer rises up as a creator, leaving society’s expectations out of her content and treating poetry as an end in itself. For Vicente Huidobro, poetry must meet three conditions: to create, to create and to create. And Ángela Álvarez creates pure beauty, she creates a new plastic language and she creates an addiction to her verses.

The poetry of De conjuros y ofrendas (Of Spells and Offerings) is without a doubt a being with a life of its own in constant transformation, in its Kafkaesque sense – a transformation causing evolution and change in those who reach for it, either subtly, or by force.

Mª Carmen de Bernardo Martínez

Translated by Jess Parsons

La orden negra - José Calvo Poyato

Al atardecer de las amapolas - Rafael Luna García

Poppies are wild flowers with very delicate petals, Rafael Luna García puts this same delicacy into each verse, each rhyme, each poem, which emerges from the centre of his being; his heart. This forms Al atardecer de las amapolas. Rafael adds passion and peace, hope and excitement to each verse, each rhyme, each poem, therefore his poems don't wither like fragile poppies, but instead they are forever etched into the reader's soul.

Rafael Luna’s poetry has a soothing effect, just like the poppies. His poems calm, ease and soothe. Like poppy seeds which are used as seasoning, Rafael’s poems season the existential doubts of the human being. According to the magical legend about poppies, the reader will fall for Rafael’s poems once they read them. They will go back to them time and time again, not only to admire the beauty, cadence and rhythm of their words, but also to make sense of love, solitude, hope, pain and of God within them.

Rafael Luna is a master of expression and uses literary devices with expertise worthy of a poet of his calibre. Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer’s influence is evident in many of his poems, feeling the romantic poet’s expression of passionate love under your own skin. In others, you feel the simplicity of life reflected by poets like Federico García Lorca, to whom his poem “Nana de las estrellas” is dedicated. Many of his other poems have bucolic shades in communion with nature, he finds peace, love and truth. Rafael Luna reflects the sky and the stars, the sun and the moon, green spaces and different animals.

The external structure of his poems bring calligrams to mind. Rafael Luna plays with the layout of the verses and breaks the traditional meter to give them new shapes, full of finesse and elegance, which give life to thought-provoking silhouettes in keeping with the poet’s feelings. These shapes take the reader by the hand down the path made up of his words, which leads to the search for the truth. The contrast between the different lengths of the verses reminds us of the daily ups and downs of life. The outline of his poems is malleable; it is defined as life goes by, in the hands of the potter.

The use of ellipses to transmit the uncertainty of life, the worries and fears that intertwine during its course is characteristic of this poet. And what's more, the writer breaks with the traditional use of this punctuation mark to create an image typical of his poems, to express feelings at the highest level of abstraction, at the maximum level of love, letting everything that is hidden behind the soul flow. Rafael Luna breaks the rules to create aesthetics.

Parallels, alliterations, metaphors, personifications, linking devices (sublimes) and enjambments are, among many others, some of the literary devices which he wisely and skillfully wield in his poems. The Moon is a fundamental symbol here, which turns into his partner, his confessor, his friend, his solace, his search, his reflection. The presence of poppies also adds a splash of red to his poetry book The repetitions create a melodic cadence which turn his words into music to the ears. And in line with the Moon and in contrast with the red colour of the poppies, Rafael Luna plays with the colour white throughout his entire poetry book, as a symbol of purity and innocence, a symbol of honesty.

The themes are recurring: the expression of feelings, the search for God through Faith, overcoming solitude, anguish and fear. The search for shelter, finding comfort. Life is a pilgrimage in a quest for truth, beauty and love, in order to be guided towards the light and God. Understanding the past to understand the present and moving forward into the future, being fragile and ephemeral like poppies. To feel loved. Creation of life. The absence of love, tears and disappointment. Beautiful descriptions of loved ones. Silence is like a moment of catharsis and finding God.

Rafael Luna García's poetry has values. You can clearly see this in his poem “Recuerdos”, where he clearly states with complete exquisiteness that beauty is always found in a human being from within. His primary values are clear: hope, love, life, faith and God, in order to be able to balance and beat rage, injustice, solitude and disappointment. Rafael Luna is a warm-hearted poet who leaves his readers or listeners speechless by using his own words, to fill them with sensations that travel through the skin and feelings which flood the soul.

“La rosa que quería volar”, a poem which closes this magnificent book is of unique beauty, it moves you to tears and evokes smiles, it distresses you, fills you with life, lifts you and allows you to fly. Full of intense lyricism, with notes of suspense and anxiety, it leaves you, once more, speechless.

Finally, as the poet himself says, he trusted that “the spirit of this book resonates, cherishing the fragility of the poppies at sunset...”

Mª Carmen de Bernardo Martínez

Translated by Sinead Rowley-Smith